The Great Parenting Lie of Our Time

Smartphones are the defining parenting issue of our time. The advice parents are given is designed to fail. Here is better advice.

Since 2010, rates of major depression have skyrocketed—up 145% among teenage girls and 161% among boys. Anxiety rates have nearly doubled as well. Smartphones and social media are the primary culprits.

Around this time, relentless smartphone use became the defining feature of adolescent life. Between 2010 and 2021, the average time 15-24-year-olds spent with friends plummeted from over two hours a day to less than 45 minutes. A recent Sapien Labs study involving 27,969 young adults worldwide provided further evidence of the link between smartphone use and declining mental health. The study found that “the later in childhood young adults first gained access to a phone or tablet they could carry with them, the better their mental well-being as adults.”

While skeptics remain, most Americans now agree that today’s smartphone culture has played a significant role in the steep decline of young people’s well-being. This sentiment has gained traction, fueled by Senate Judiciary hearings with social media executives and the Surgeon General’s warnings that 13 is too early for teens to be on social media.

Parents today are more aware than ever of their responsibility to limit how their children use screens—a welcome shift compared to just five years ago. But this progress alone isn’t enough to reverse the alarming mental health trends we’re seeing. It’s not enough because the guidance parents have been given to address these issues is, well, useless.

“Try This Solution that Won’t Work…”

Parents who express concerns about how to deal with smartphones, social media, and screen time are met with a lot of advice, but one standard response reigns: Make a family media plan!

You’ll see this advice parrotted in articles, PSA’s, and school district-run parent-education programs. I’ve offered this advice, myself, both in my book and during parent education talks. But weeks ago, it hit me:

I’m out here recommending family media plans, yet I don’t have one—and I don’t know any parents who do. Do you?

The family media plan option sounds right. Its empowering and aligns with the popular belief that parents know what’s best for their children—or at least that they should get to decide what is best.

But this is exactly what smartphone and social media companies want us to promote. They are eager to suggest family media plans, and they’re thrilled that school districts, government agencies, and parenting blogs follow suit because they know it won’t make any real impact.

Telling parents to deal with the infinite capacity of the smartphone by making a media plan is a bit like saying:

Youth obesity has tripled since 1990 and over 57% of today’s youth are projected to be obese by the time they are 35. Let’s combat this issue by suggesting that people do some online research and then make a personal diet and exercise plan. That will work well, right?

Of course not. If you want to actually help people, you don’t say:

All you need to do is set aside a large chunk of time to do a very abstract planning activity. In said activity, you will need to make educated guesses about how you might limit technologies that you don’t completely understand. You’ll need a firm grasp of the principles of motivational psychology and behavior change (topics which aren’t taught in school).

Oh and, by the way, no one else that you know will be doing this activity. You’ll be the only one making a family media plan. When you finish making your plan, you will have set limits and boundaries that you think might help protect your family against the most brilliant minds in Silicon Valley. But you will need to enforce these despite the fact that everyone else you know does not.

This hasn’t worked and it won’t work.

Likewise, Family Media Plans sound great, but they don’t work. And that is exactly why social media companies love them.

Maybe You Should Just Try Harder

The genius of the “personal responsibility” argument is that it is hard to disagree with. Our country is founded upon an expectation of personal responsibility, which is an inherent requirement of both freedom and representative democracy.

Our American ethos primes us to believe that:

Each individual parent should be responsible for governing their children’s screen time, just as every individual should be responsible for governing his or her own.

We are all responsible adults living in a free country.

We should all be free to decide how we will use smartphones, social media, and screens, in general. We should be free to set up our own systems so that we stay within the limits we’ve defined, and we should be empowered to decide for ourselves how our children will use them.

I don’t entirely disagree.

Parents should limit the role of smartphones and screens in their kids’ lives. But framing the problem as one of personal responsibility alone is misleading.

The chief aim of this ploy is to isolate and atomize individuals. This narrative sets parents up for failure by ignoring the need for interventions that actually work—those rooted in environmental change, community action, and collective support.

It’s a time-honored tactic, designed to keep people hooked on addictive products while shielding the industry from accountability.

The Origins of Using Personal Responsibility as a Form of Manipulation

It seems reasonable to assume that “personal responsibility” was always the default argument when it came to potentially addictive and self-destructive products like cigarettes, junk food, and social media. However, Big Tobacco didn’t lean into this argument until 1977. As explained in a revealing analysis from the American Journal of Public Health:

“... the tobacco industry rarely raised personal responsibility in news coverage (in the 1950s and 60s), instead denying that its products harmed health…

Industry representatives began to regularly use these arguments in 1977. By the mid 1980s, this frame dominated the industry’s public arguments.”

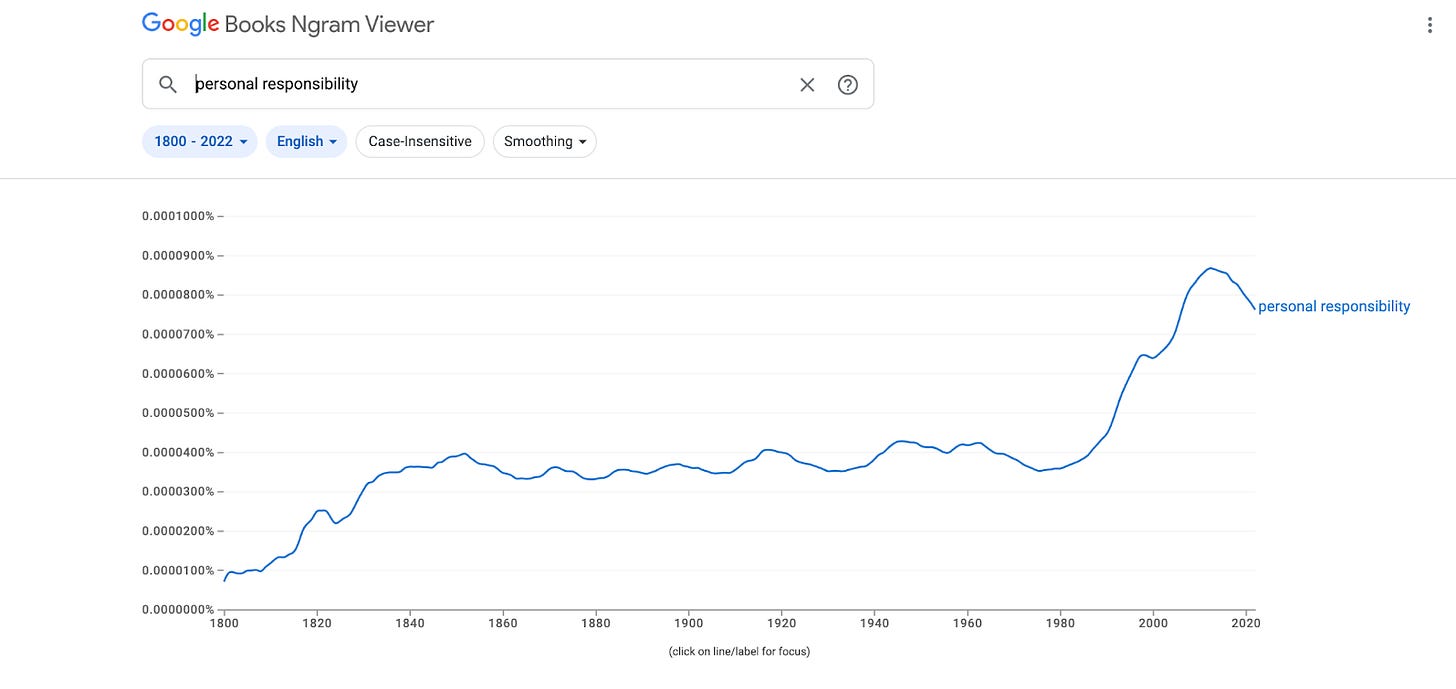

The effectiveness of these campaigns is evident from Google Ngram’s data on use of the term “personal responsibility” over time.

The cigarette companies, like the junk food companies and tech giants who followed them, have consistently sought to frame smoking as solely an issue of personal responsibility and freedom of choice. They remind us that it is our right to decide if and when we will use their products. They simply provide a service that people want.

This sets up a false dichotomy, which prevents us from adapting better to our modern technologies: You are either for freedom or against it.

That false dichotomy recasts reasonable steps, like asking social media companies to confirm the ages of its users, as egregious government overreaches which trample our freedoms and defy the core tenets of our great nation. Most often, however, that is not the case.

More still, that faulty reasoning relies on a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of our technology and how we best honor our citizens’ freedom to choose.

Baked into this deception is the illusion that we all get to choose how we use technology. But that isn’t exactly true.

Do You Really Have a Choice?

Technically, you have a choice about whether to put your money in a bank, or not. But if you decide not to put your money in a bank, you will be unable to participate in most basic societal functions. Choosing not to have a bank account is choosing not to be a part of society.

The same is becoming the case for smartphones. From a very young age, society imposes the expectation that we all have a smartphone.

For example, to purchase tickets for a middle school basketball game in my local school district, students have to use an app called Ticket Spicket and then show their digital ticket to the “ticket taker.” There is no way to do this on an internet-free flip phone and the district does not offer a backup system for students who don’t have a smartphone. You can’t even purchase and print your ticket from a computer at home.

Thus, 12-year-olds (and their parents) are placed in a situation where they must either have a smartphone to get into a basketball game, or be forced to attend each game with mom, so she can show the “ticket taker” the digital ticket on her phone. By not having a smartphone, students lose out on exciting opportunities, like riding to the game with a friend and his parents, or walking down the road to the game with a group of friends. Understandably, many parents give in and buy their kid a smartphone, even if they wanted to wait until later, because they want their child to participate in basic middle school functions.

Likewise, many would say that every kid with a smartphone has the choice of whether to lie about their age and create a Snapchat account, or not. But when you are 12 and all of your friends are sending each other hundreds of “snaps” each day, the choice is made for you. Given this pressure, what 12-year-old wouldn’t lie about her age and join Snapchat?

Our environment pushes all of us towards many choices, whether we want to make them or not. Over and over again, communities pressure parents to make the wrong choice about when to give their kids a smartphone and they pressure students to make the wrong choices about how they will use those devices.

But at least these are choices that we are aware that we are making. Smartphone designers have worked hard to eliminate conscious choice-making opportunities. To use a smartphone is to subject yourself to a barrage of choice manipulations.

The Take Home Message

The chief aim of the great lie is to isolate and atomize individuals, rather than support them with interventions that can actually work. Any attempt to actually help reverse these trends must adhere to three primary principles of effective behavior change:

Make it simple: Make the desired behaviors simple and clear. Script out the specific actions that people need to take (e.g. don’t give your son or daughter a smartphone until high school).

Make it social: Make the desired behaviors normal. Utilize social pressure (e.g. schools should ban phone use throughout the school day and recommend that parents don’t give their kids a smartphone until high school).

Make it easy: Craft the environment so that the desired behaviors become the default behaviors. (e.g. change laws so that young-adults cannot have social media until age 16 and require social media companies to enforce this).

In his latest book, The Anxious Generation, Dr. Jonathan Haidt promotes a set of new community norms that take advantage of the behavior change principles listed above. Among these are:

No smartphone before high school (you can give students an internet free flip phone before high school if it helps promote their independence).

No social media before 16.

No phones allowed throughout the school day (all phones go into phone lockers or Yondr pouches).

Let’s briefly look at each of these suggested norms beginning with the most obvious and actionable of Haidt’s suggestions: No smartphones in school.

Get Smartphones Out of Schools

A recent study showed that students who had their phone on their desk performed worse on working memory and fluid intelligence tests than students who kept their phones in a backpack by their side. More still, those students who kept their phones in a backpack performed worse on these tests than those who stored their phones in another room. The further students are from their phones, the better they will learn.

But this is not just a learning issue. As Dr. Haidt explained at the 2023 Summit on Education: “It is not just academic progress that tanks when kids have phones in their pockets. It’s also social belonging and inclusion.”

Parents and educators must begin to demand that our schools remove access to smartphones throughout the school day.

Too many school leaders have tried to avoid conflict by remaining neutral on the topic of smartphones. This is a dereliction of duty. To remain neutral is to compromise the culture of your school and guarantee that your students' attention and wellbeing are ravaged by the smartphone.

This brings us to the next norm: No smartphone before high school.

Don’t Give Kids Smartphones Before High School

When parents are asked to identify their top fear for their kids, the most common answer is internet/social media. But the internet and social media are, both, far less threatening when they can only be accessed at a computer in a family common area. It is the smartphone that makes these networks so dangerous and hard to limit.

Despite their fears of the internet, most parents will give their children a smartphone before they’d like to because: “all the other kids have one.” Social pressure pushes parents to cave into their child’s pleas.

Haidt recommends that all parents begin waiting until high school to give their kids a smartphone, just as many tech moguls already do with their kids. Opt for an internet free flip phone before high school.

But this differs from the more typical “you do you” parenting advice, like this from a recent Washington Post article:

There is no magical age when tweens or teens are ready for a smartphone. Each child develops at a different pace and comes with their own personalities and struggles. Parents and caregivers also have different ideas of what’s appropriate for their families…

Your children could be ready for a smartphone or similar device anywhere from 10 to 14, or during middle school. A sixth-grader (typically 10 to 11 years old) is a good age to start discussing a phone or a smartwatch.

There are valid reasons to go younger…

See how this advice aligns with the great parenting lie? Every parent can do whatever they deem appropriate. This is completely nonjudgmental and completely harmful to the interests of the majority of parents who want honest solutions for their deep fears.

While it is true that every student matures at different rates, this doesn’t mean that it is beneficial for any 8th grader to have a smartphone. There is no reason to believe that a very mature 8th grader would be harmed by not getting a smartphone until high school. However, there is plenty of reason to believe that even a very mature 8th grader will be better off waiting longer to get a smartphone.

Much of this pressure to be nonjudgmental stems from a desire to avoid offending those many parents who have already given a smartphone to their kids well before high school. To help parents do what is best for their children, we have to stop worrying about making some parents feel bad. A lot of very good parents have given their children a smartphone at too young of an age. They did so because that was the norm their environment promoted. We can understand why many parents have not waited until high school in the past, while also noting that we now believe parents should wait until high school to give their kids a smartphone.

Change the Legal Age for Social Media to 16 and Enforce It

Right now the legal age to begin using social media is 13, but there is no age verification. Anyone can create an account. It doesn’t have to be this way.

I can’t open a bank account, get a driver’s license, or enroll my children in school without identity and age verification. We could easily do the same for social media. These are the most brilliant and innovative companies in the world. They can figure out how to do this.

And there isn’t anything radical about identity and age verification. It doesn’t violate any adult freedoms. It establishes a research-supported minimum age which is as reasonable and enforceable as the age requirements we already have for driving, voting, and drinking.

Reason for Optimism

The only reason these common-sense initiatives have not yet been widely adopted is because of the great lie. But parents, educators, and community leaders are starting to see through it.

As an educator, I spent a decade advocating for smartphone bans, often wondering if my efforts were in vain. Then, unexpectedly, my school district passed a phone ban in classrooms. It isn’t perfect but it represents real progress and it is representative of a larger movement.

Just last winter, the UK government issued guidelines effectively banning mobile phones in all public schools across England, and, likewise, the Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second-largest, followed suit, banning phones and social media use throughout the school day. By the end of 2024, at least 19 states had passed laws or policies to require or promote smartphone bans. This demonstrates what can happen when parents recognize insane norms, voice their opinions, and work to promote change. This is what happens when community leaders recognize the power of environment and their responsibility to foster an environment where young people can flourish.

The great parenting lie of our time is that each parent should independently figure out how they will introduce the smartphone and social media to their kids—that we should respect every parent’s choice as equally valid. This nonjudgmental language sounds nice, but it perpetuates insane norms. It perpetuates a culture where eleven-year-olds badger their parents because they feel they are the only ones who do not have a phone and where fourteen-year-olds spend half their school day on their phones.

It is time for parents, educators, and community leaders to recognize the deception and demand that we do what is right for our kids. That is what a responsible people would do.

Thank you for reading and sharing!

Carry the fire!

Shane